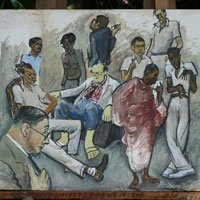

Anukshi Jayasinha, courtesy of Ceylon Today online where the title is “Th Rebels of ’43″… see http://www.ceylontoday.lk/64-14169-news-detail-the-rebels-of-43.html where more illustrations of their work can be found.

In 1943, a young, restless group of artists came together to tear down the rigid and only form of art that was appreciated at the time in Colombo. What started as small, frequent gatherings of a few like-minded individuals soon expanded and flourished, creating a lasting impact on the art scene in Colombo and changing it forever. The ’43 Group was one of the most influential movements in Sri Lankan contemporary art, and its artists and their work are of utmost value, both in Sri Lanka and internationally.

Rejected misfits: In a transcript for a radio programme that aired on Melbourne Radio 3EA, the late cartoonist Aubrey Collette writes: “In the bad old days in artistic activity, it was controlled by two reactionary bodies—the Atelier School owned by A.C.G.S. Amarasekera and Ceylon Technical College by J.D.A. Perera, and they represented the sum total of Western art in the land.” He adds: “From time to time, individual artists had tried to rebel against the tyranny of traditional painting, but so strong was the stranglehold that their efforts were only met with derision.” Photographer and patron of the arts Lionel Wendt had tried to introduce the work of George Keyt and Geoff Beling, but the “press critics dismissed them as a couple of misguided eccentrics.”

In the years before the formation of the ’43 Group, most of its core members spent many years studying art and travelling throughout Europe. Through the mentoring they received and friends they made, they were able to open up to different, innovative forms of drawing and painting. Harry Peiris enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art in 1923, at the age of 19. He returned to Ceylon for a couple of years in 1927 only to leave to Paris again, where he was tutored by Robert Falk. Paris at the time was an exciting to place for artists to be in, and Peiris worked closely with world-renowned painter Henri Matisse. “The other members of his family were encouraged to study, but Uncle Harry was allowed to do whatever he wanted to in Paris,” says Damiyanthi Peiris, niece of the last portrait artist.

Justin Deraniyagala, who initially studied law at Trinity College, Cambridge, United Kingdom, enrolled in the Slade School of Art in London. He also travelled and worked in both London and Paris, and often met up with Peiris while abroad. Both were influenced by artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Georges Roualt, and Matisse. Lionel Wendt, a barrister by profession who studied law in the United Kingdom, was also a Professor of Music from the Mark Hambury School in Berlin. Collette described him as a “world-class photographer, and although he did not paint, had a prodigious knowledge of art, both Western and Oriental.”

Damiyanthi remembers Wendt bringing back “facsimiles of Impressionist paintings of the greats” upon his return to Ceylon. Collette, who was sent for painting lessons to David Paynter, soon met the master’s only other pupil, Ivan Peries. Both never studied in Europe, but were producing exciting and innovative work. According to Collette, Peries was “obsessed with the idea of rounding up all the artists who had been rejected by the Academy and starting a rebel group. To this end, he made a list which included many who had disappeared into obscurity and persuaded them to take up their brushes again.” Together, Collette and Peries went to visit Wendt who understood their cause. Peries proposed a list of names for the new ‘rebel’ group: Keyt, Deraniyagala, Beling, George Claessen, Richard Gabriel, and Collette and himself (L.T.P. Manjusri was also included in the core group), all of whom were approved of and formed the original ’43 Group.

Doing it on their own terms: The group’s inaugural meeting was held on 29 August 1943 at Wendt’s home on Guilford Crescent, Colombo 7. The group’s first exhibition was held at an old warehouse on Darley Road in Maradana, in November 1943. In his talk at the Colombo Art Biennale early this year, Chairman of the Sapumal Foundation, Rohan de Soysa, revealed the nature of the public reaction to the exhibition: This first exhibition was greeted with derision and scorn by the staid and conservative art world of Ceylon, much as the Impressionists had been in Europe decades earlier. Some unkind comments were, “Some people were more thrilled with the titles of the pictures than by the pictures themselves”; or “My strongest impression of this exhibition was that it was conceited.” He also noted that a ‘kinder observer’ wrote: “It was a stimulating relief from the usual pictures of old men with long beards, temple elephants and flamboyant trees. There are at least half a dozen works that would do honour to any exhibition anywhere in the world and more than three times that number of exhibits that would repay the closest attention.” Collette noted: “The reception was mixed – a select few were appreciative but mostly the reaction was hostile. With one or two exceptions, the press produced the usual ignorant criticism and did their best to denigrate us.”

The artists of the group were at liberty to select their own work for exhibitions, and whatever they chose was always exhibited. “There was no regimentation; it was up to them. Their exhibitions were self-censored. They decided what was to be exhibited,” says de Soysa, speaking to ‘Ceylon Today’. Nevertheless they adhered to the highest aesthetic standards and remained an exclusive group, welcoming only the very best. They were primarily influenced by the Impressionists and Expressionists of the Western world. All core members came from diverse backgrounds and each produced work with a distinct style that was appreciated within the group. “The most remarkable thing about the Group was that it was made up of artists who were so diverse in style and temperament. We were by no means a school of painting in the sense of the Impressionists in Paris or the Heidelberg School in Australia. Each member had his own individual style and outlook, and yet we held together as a cohesive hold,” noted Collette.

Following the demise of Wendt only a year later, the activities of the group came under the guidance of Pieris, who in addition to being an artist was also a great patron of the arts and was the “greatest single influence on the younger painters”. Meetings were moved from Wendt’s house to Pieris’ living quarters at the back of his mother’s home. “They met frequently, and once a month, they welcomed anyone who wanted to join them – even monks and politicians – and come talk about anything related to art,” says de Soysa. The group continued to hold regular exhibitions, at the Darley Road warehouse, the Art Gallery, Lionel Wendt’s house and at the Lionel Wendt Centre. By 1967, the group had held 16 exhibitions locally.

Worldwide recognition: Soon they began exhibiting abroad, and this time, they were received and appreciated much better. At an exhibition held in South Kensington, London, in 1952, critics particularly noted the great skill and potential in Keyt, Deraniyagala and Gabriel. In 1953, the group exhibited at the Petit Palais in Paris, where someone commented: “What characterizes this school and makes it a living thing, is the degree of accomplishment in forming a synthesis between an age-long tradition and the twentieth century ……… they form, very certainly, the foundations of a great art: they mark a beginning only, but a beginning of plenty and hope.” Gabriel’s painting ‘Fighting Bulls’ and Peries’ ‘Portrait of Iranganie’ were bought by the Musée du Petit Palais. In 1955, the group exhibited at the Venice Biennale, where Deraniyagala won the UNESCO prize. Following the London exhibition, an editorial in ‘The London Times’ hailed the group as “spearheading a Renaissance in Asian Art.” The group continued to exhibit all over the world, including Sao Paulo and Florence, and their international recognition was attributed to Ranjit Fernando, the group’s youngest painter, who tirelessly organized these exhibitions.

However, following the late 1960s, many of the members of the core group began to retire or leave the country. “There was a change in the social climate, and many of them decided to migrate,”says de Soysa. Keyt moved to Kandy, while Claessen and Gabriel emigrated. Beling retired. Collette, who was adored by the Sri Lankan public, was regarded as controversial by the government at the time, leading him to migrate to Australia in 1961.

Sapumal today –Pic by Dumith Wanigasekera

Sapumal today –Pic by Dumith Wanigasekera

Sapumal: Pieris, until his death in 1988, continued to support and influence the art of painters in Sri Lanka. He had lovingly built a large collection of paintings by the members of the ’43 Group, and encouraged young artists by mentoring them and aiding them financially. “He was never jealous; he was humble and open. He was tireless in promoting other people’s art; he was glad to do so,” recalls Damiyanthi of her uncle, who taught her to break away painting still-lifes and produce naturally and spontaneously. Wanting to further Sri Lankan art and open up the group’s work to the public, he established The Sapumal Foundation in 1974 at his home on Barnes Place with two friends, Dr. Christopher Raffel and Dr. Arthur Weerakoon. It was named after the affectionate nickname he was given as a young boy by his family, Sapumal, and was often the location for salons and tea parties for discussions on art, culture and current affairs.

A voracious reader, Peiris also collected books on almost every topic, and carefully preserved them in his library, which now serves as the library of the gallery. Adorned with a large collection of paintings, photographs and illustrations of both core and late members of the group, the foundation serves as a centre for the education and appreciation of the intriguing beginnings of contemporary art in Sri Lanka—and the inspiring story of a group of young artists who came together to revolutionize, innovate and support the growth and deeper appreciation of Sri Lankan art and artists.

(Sources: Photo of ‘43 Group illustration: www.thuppahi.wordpress.com. Collette’s radio transcript courtesy Cresside Collette, Melbourne, Australia)

ALSO SEE http://www.ceylontoday.lk/35-11996-news-detail-elements-of-an-art-lover.html